Scalable System Architecture

Case 1: The Trap of a Seemingly Scalable System Architecture

Why does this system architecture pattern seem cost-effective and infinitely scalable but is actually a massive trap that you should avoid at all costs? Please do not fall for this one unless you know the intricacies of this pattern. Why might I use this pattern for a toy side project that will likely never have any users or maybe just a handful of users? The reason might not be what you think. This is also one of the patterns I might use for applications that need to scale—those that need to handle hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of users. So, let’s break all this down.

This basic system architecture is what everyone starts with, and there’s a pervasive argument that the vast majority of apps don’t need anything more than this. That’s kind of true, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you should build this way. We’ll get to that.

In this scenario, you might not have an automated build process. Instead, you build on your local machine and manually copy the binaries to the host that will serve your application. Your scalability in this situation is limited to upgrading your cloud instance to a bigger one. To be fair, in terms of the ability to handle traffic, you could probably get pretty far with just one of the largest cloud instances available.

However, if you need to upgrade your infrastructure, you’re going to experience downtime. Even worse, every time you update your application, you’ll have downtime because you need to stop everything, copy the new binaries to the instance, and start your app again. Of course, that might not be a big deal if your original assertion that you don’t have many users is true.

In summary, this architecture pattern, while seemingly scalable and cost-effective, has significant drawbacks, especially concerning downtime during updates and infrastructure upgrades. This might be acceptable for small projects with minimal user bases, but for larger applications, its limitations could be problematic. Carefully consider the long-term implications and hidden costs of such architectural decisions.

Case 2: The Evolution to CI/CD

The next evolution in system architecture is adding CI/CD, or Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment. I almost didn’t mention this because, in this day and age, pretty much everyone is on board with this one. The lines between CI and CD can be a bit blurry, but generally speaking, here’s the breakdown.

Continuous Integration (CI):

- Automated Builds: When code is committed, an automated build is triggered. This means every time you push a change, the system compiles the code automatically.

- Automated Tests: After the build is complete, automated tests are run to ensure the new code doesn’t break existing functionality.

- Notifications: Developers receive notifications if either the build or tests fail, allowing them to quickly address issues. While CI might encompass other elements depending on the team or project, these three components form the core of CI.

Continuous Deployment (CD): Once the build completes and all tests pass, an agent automatically deploys the new application binary to the hosting platform. In this example, the deployment target is a plain EC2 instance. Often, automatic deployment first happens to a test environment rather than directly to production. Automated integration tests might run in this test environment to verify the application’s functionality in a setup that closely mirrors production.

Continuous Deployment vs. Continuous Delivery:

- Continuous Deployment: If the new binary is automatically deployed to production after passing the tests, this process is called continuous deployment.

- Continuous Delivery: In many cases, there is a manual approval step between deploying to the test environment and deploying to the production environment. If a human needs to approve and manually trigger the final deployment to production, it’s termed continuous delivery instead of continuous deployment. In summary, CI/CD represents a crucial evolution in modern software development, streamlining the process of integrating and deploying code changes. By automating builds, tests, and deployments, CI/CD helps maintain code quality and accelerates the delivery of new features and fixes, with the key distinction between continuous deployment and continuous delivery being the presence of a manual approval step before production deployment.

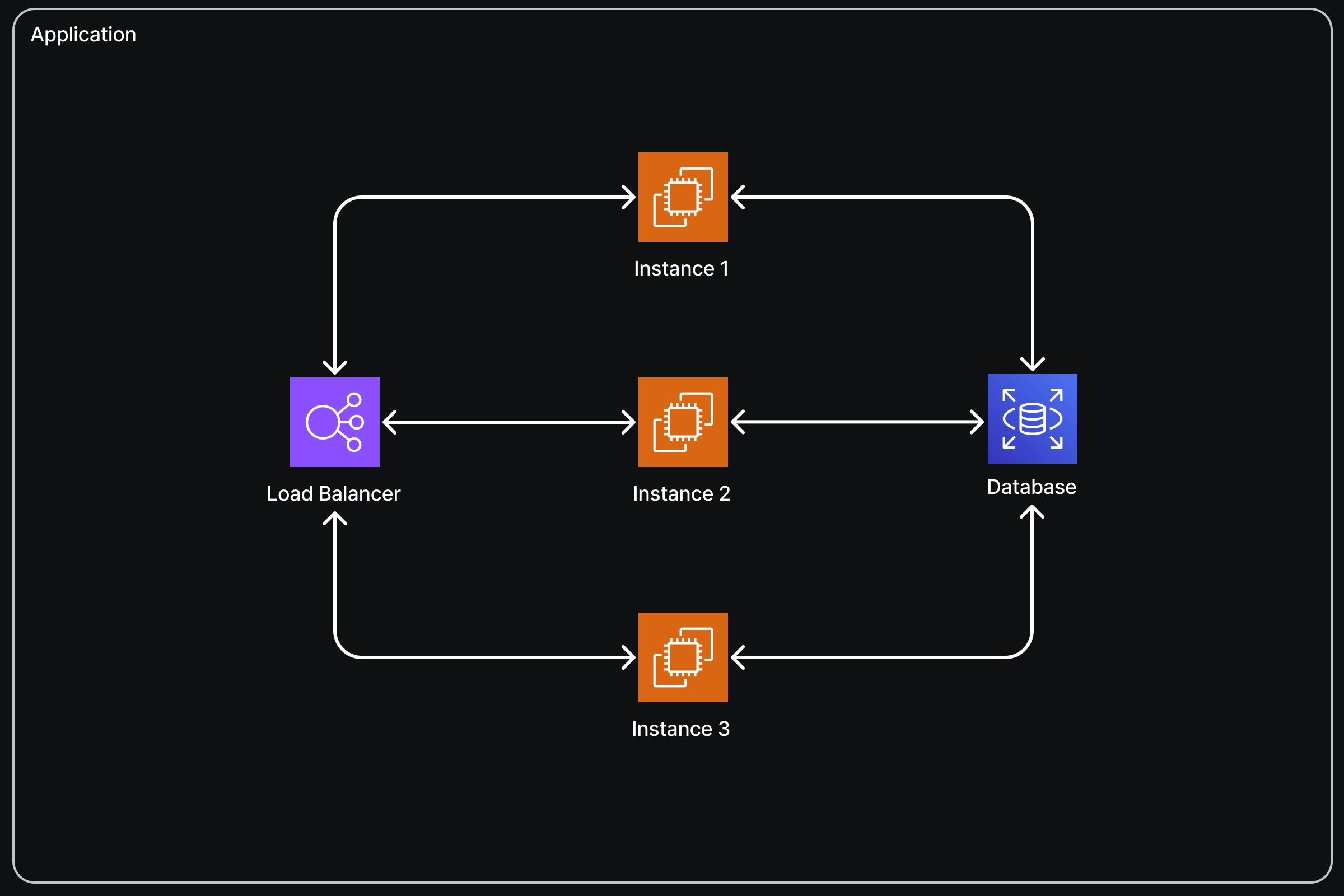

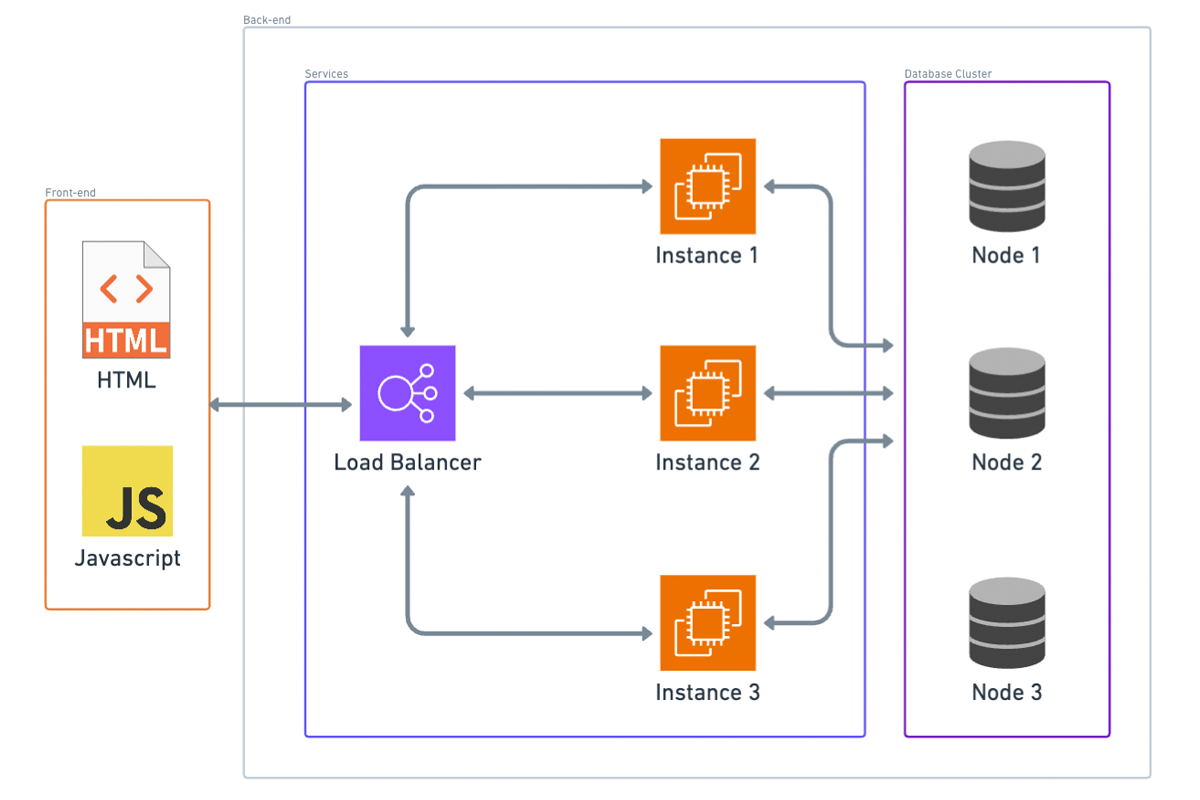

Case 3: The Advantages of Managed Hosting Platforms

Now we start to get into managed hosting platforms. There’s nothing here that you couldn’t technically do manually, but the platform makes it way, way easier. Frankly, nobody I know of does this stuff manually anymore.

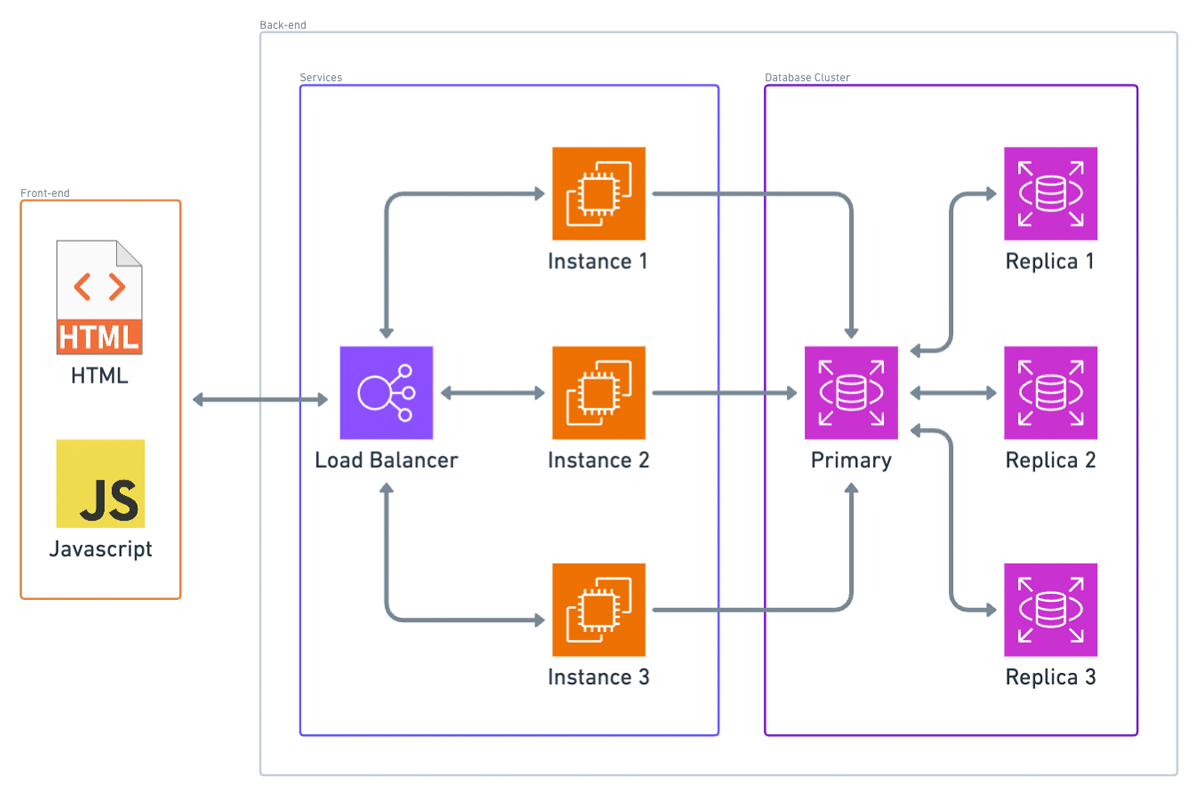

With managed hosting, we have a load balancer. The external world connects to your app through this load balancer, which distributes requests between one or more instances, each running your application. Here are the benefits:

1. Handling Higher Volume of Requests:

Your application can now handle a higher volume of requests than it could with just one instance. The load balancer distributes requests among the running instances using various strategies. Interestingly, random distribution of requests usually works fine.

2. Stateless Application Requirement:

For load balancing to work, your application needs to be stateless. This means it shouldn’t matter if different instances handle the client’s requests each time. Therefore, you can’t use in-memory caching or similar techniques that rely on state being preserved within a single instance.

3. Automatic Scaling:

Many deployment platforms, including AWS Elastic Beanstalk, support automatic scaling. This means you can set up rules for when scaling should happen, based on metrics like the number of requests or CPU usage. When the threshold for a metric is reached, the platform automatically creates another instance, deploys your application on it, and registers that instance with the load balancer to handle higher traffic volumes. For example, if three instances aren’t sufficient to handle the current traffic load, the system can automatically create a new instance, making a fourth instance. This fourth instance is then added to the load balancer, ensuring requests are distributed evenly across all four nodes.

In summary, managed hosting platforms offer significant advantages by simplifying tasks such as load balancing and scaling, allowing your application to handle increased traffic seamlessly. These platforms automate complex operations, enabling you to focus on developing your application rather than managing infrastructure intricacies.

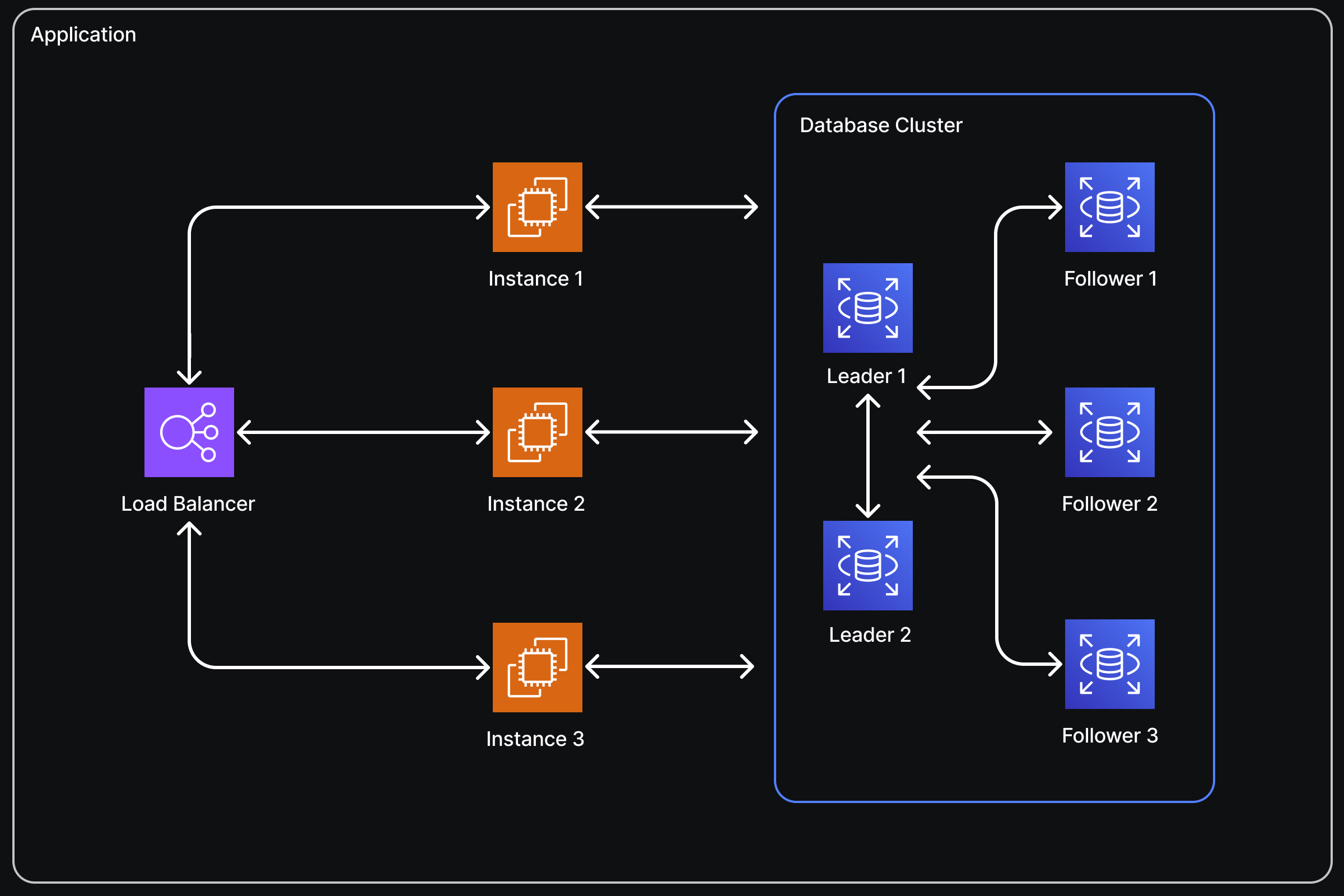

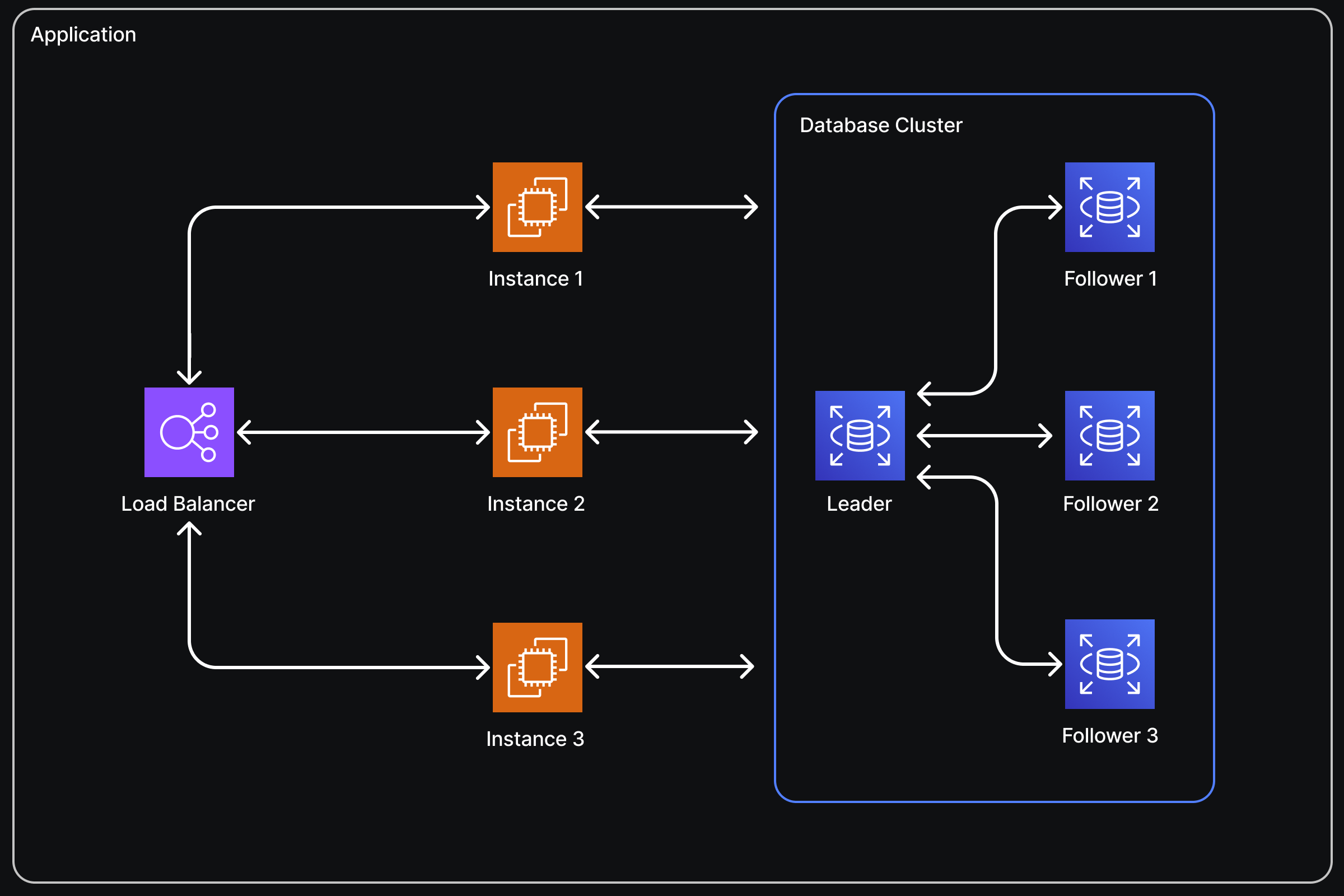

Case 4: Scaling the Database

At this point, we’re in a pretty good place, but it’s easy to see what the main bottleneck is now: the database. Scaling the database can be tricky if you haven’t planned for it from the beginning because it can impact how you design your schema.

Two Reasons for Database Scaling:

1. Data Size:

If your application’s data set can’t fit on one instance, you’ll need to implement sharding, which involves splitting your data across multiple database nodes. This process is complex. For instance, if you start with three nodes and need to add another, redistributing the data so that each node has an equal part can be challenging.

2. Traffic Volume:

The other reason to scale up the database is to handle higher traffic volumes. This involves distributing requests across nodes, similar to how we distribute requests to application instances behind a load balancer.

Key-Value or Document Databases:

If you chose a key-value or document database like AWS DynamoDB, scaling is much easier. These databases automatically handle fault tolerance, load balancing, and sharding of your data. Although they impose some constraints on your schema that wouldn’t exist with a SQL database, if your data structure allows, you should consider using one of these databases for easier scaling. To scale up or down, you might only need to change some configuration settings, if that, because these databases often have auto-scaling capabilities.

SQL Databases:

If you opted for a SQL database, scaling becomes more complex. However, if two conditions are met, you’ll probably be okay:

- Your application doesn’t require a high volume of writes.

- Your application’s entire data set can fit on one database instance.

If both are true, you can set up a single master, multiple replica database cluster. This setup typically doesn’t require changes to your application logic. In this configuration:

- All database writes are directed to the master instance.

- Read replicas receive state updates from the master whenever data changes.

- Read queries are load-balanced among these replica instances and, in some cases, the master as well.

However, the master database instance remains the bottleneck for writes. Additionally, the entire data set is copied to every instance, so if your data doesn’t fit on a single instance, this setup won’t be effective.

In summary, database scaling is crucial yet complex. Key-value and document databases offer automated solutions that simplify scaling, while SQL databases require more careful planning and configuration, especially when dealing with high volumes of writes or large data sets.

Case 5: The Fallacy of Not Building for Scale

Now that we have our potential endgame system architecture, there’s a fallacy I want to dispel in this video. This fallacy comes in various forms but is essentially the same idea: “I won’t have any users, so I don’t need to worry about scalability,” or “This is just a side project, so it doesn’t need to scale.”

The point I want to make is that even if your application won’t scale, it should scale, but not for the reasons you might think. It’s not necessarily because you might unexpectedly get more users than you can handle (you probably won’t). There’s more to it than that.

There’s a common misconception that building with scale in mind requires extra thought and will make every project take longer. While it does require some extra thought, that extra thought isn’t really on a per-project basis. Once you internalize the basic concepts around building for scale, I’d argue that building things with scale in mind doesn’t really add any extra scope to the project. It just takes a bit of time upfront to learn the concepts, and after that one-time investment, incorporating scalability into your project shouldn’t really add any scope. That’s my take anyway, and that’s why I think even toy or side projects should be built with scale in mind.

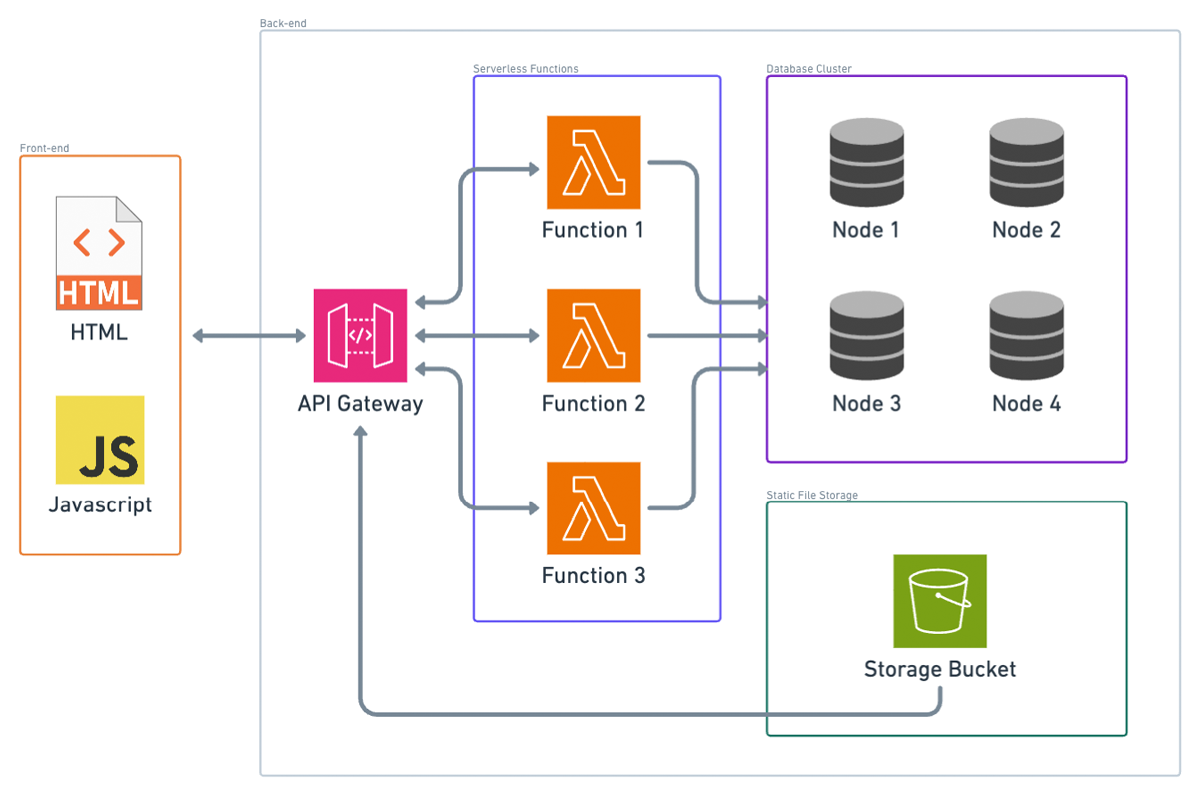

Case 6: Serverless Architecture

Next, let’s talk about serverless architecture. Here’s the serverless analog of what we’ve been doing so far. Instead of a load balancer, we have what you might think of as a lightweight proxy. In AWS, this would be API Gateway. Instead of our container platform, we have our static files (HTML and JavaScript) in an S3 bucket. For our APIs, we have serverless functions; in AWS, that would be AWS Lambda.

Notice that I took out the CDN box. You can still have a CDN if you configure API Gateway to be edge optimized, so that’s still kind of there.

Advantages of Serverless Approach:

Cost Efficiency:

If nobody’s using your application, the only thing you technically pay for is the static files in the S3 bucket and the data stored in your database (if you’re using a cloud database). If you’re using container instances, which likely use an EC2 instance per container, you’d be paying for that EC2 instance even if nobody’s making requests to it.

Elastic Scalability:

Serverless scalability is much more granular than in traditional architecture. Each instance in a container-based setup represents a certain number of requests per second it can handle. For example, each instance might handle 100 transactions per second, but if you need to handle 301 transactions per second at a certain time, you’d need four instances. You’d be paying for that fourth instance even though it’s almost not needed. Additionally, you need to set up your scaling criteria carefully. If traffic dies down and your containers don’t get spun down, you’re paying for extra containers you don’t need. Conversely, if traffic spikes and you don’t add more containers in time, you might face an outage.

Handling Sporadic Traffic:

Serverless functions excel at handling sporadic traffic. For example, if you suddenly get a thousand requests all at once after hours of no traffic, serverless functions should be able to handle it. You also pay on a per-request basis, so you’re always paying for exactly the amount of traffic you’re handling. Unless your traffic volume is consistently high, this is likely cheaper than the containerized equivalent.

In summary, even if your application is a side project or a small-scale application, building with scalability in mind can save you from future headaches and unexpected growth. Serverless architecture, in particular, offers cost efficiency and flexible scaling, making it a strong choice for many applications.